The Cultural History of Madikwe

Introduction

Madikwe’s rich cultural history began almost one million years ago and is as much a part of the reserve as the wildlife and other natural wonders in the area. Historical sites containing irreplaceable artifacts are in abundance and in time will be restored and displayed as part of South Africa’s heritage.

Stone Age

In 1996 archaeologists unearthed many artifacts dating back from the early to the late Stone Age (between 1 000 000 and 50 000 years ago). These artifacts, consisting of various stone tools, confirm that Stone Age people lived in Madikwe. Many were found close to outcrops of the stone used to create the tools, along the Marico River, close to Tweedepoort Ridge.

Iron Age

The Iron Age covers the past 2 000 years. Early Iron Age people moved from the Nigeria/Cameroon area between 200 BC and 100 AD, down the east coast of Africa to as far as the Eastern Cape. Sorghum and millet cultivation, livestock farming, pottery making and metal smelting gave these people more control over their daily and longer-term existences. The economic and social advantages of this more stable lifestyle allowed for larger family groups, which caused a southern migration to less densely populated areas.

The Middle Iron Age people started to arrive in the Dwarsberg/Marico River region after 900 AD. The oldest Iron Age pottery found in Madikwe is from the Eiland phase of Kalundu dating back to between 900 AD and 1300 AD. One site is in the Dwarsberg on the eastern side of the reserve and a second site is in the Tweedepoort Ridge, a few kilometres east of the Wonderboom Gate.

Their huts were cylindrical, with mud-plastered walls and thatched conical roofs. Cattle enclosures and fences around the settlement are made from thorn tree branches. Sorghum, millet and other crops were grown on the settlement’s perimeter on good soils that could be cultivated with a hoe. Building of the thousands of interlinked circular stone walled structures, which can be seen today, began in about 1600 AD.

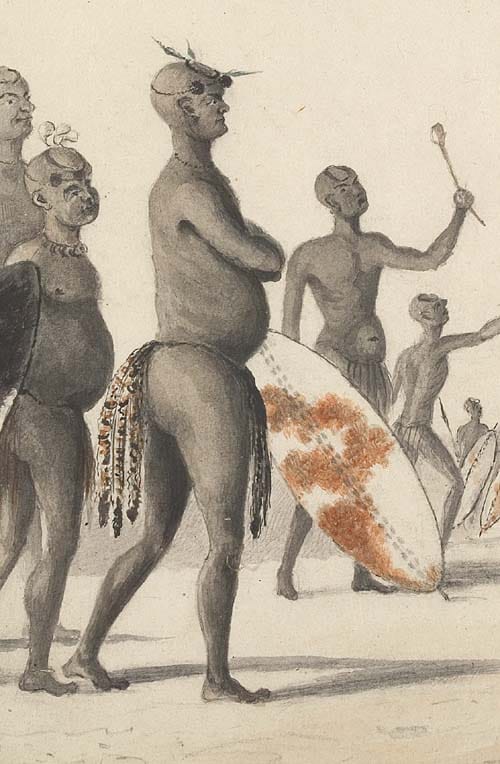

![By John Campell (1766 - 1840) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.madikwegamereserve.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/Campbell-Thlapingkaptein.jpg)

By John Campell (1766 – 1840) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Sotho-Tswana People

From about 1300 AD to 1420 AD the climate was colder and drier than today because of the effects of the Little Ice Age. During this time Sotho-Tswana people started moving south from East Africa.

Sotho-Tswana pottery, called Moloko, dating between the 15th and 17th centuries has been found on red soil patches at the base of the Tweedepoort Ridge and along the eastern half of the Dwarsberg. In Madikwe, the red soil was preferred to the black clay as it could support sorghum and millet agriculture and provide a stable foundation for huts.

One well-preserved site, next to the Phofu Dam, consisted of cattle byre, sorghum grindstones and several exposed hut floors with portions of moulded benches, a characteristic of early Moloko huts.

Some early Sotho-Tswana settlements contained late Stone Age flakes and scrapers, indicating that San people probably worked in the homesteads.

Among the first Sotho-Twana groups to arrive in the area were the Hurutshe people who settled along the Marico River. Their main settlement, Kaditshwene, south of Madikwe, eventually became one of the largest towns in Southern Africa. In 1800 AD, its population was estimated to be around the same as Cape Town’s at the time. After some time the Hurutshe subdivided and the offshoots moved east towards the Magaliesberg.

The Difaqane/h3>

The Difaqane (or Mfecane) was a period of unrest in South Africa, which, in Madikwe, forced Sotho-Tswana people to move their homesteads to the tops of the hills and live in large settlements for defensive reasons.

It probably started years earlier when the Portuguese introduced maize into Southern Africa. The Nguni people in KwaZulu found that maize was easier to cultivate than other African grains and hence more food was produced and populations grew. Consequently, more land was sought. In 1821 several Nguni clans moved over the Drakensberg to escape the Zulu expansionism. They attacked and displaced the BaTlokwa in the Caledon area, which then had a ripple effect through to the Magaliesberg and Dwarsberg areas.

It also appears that around 1810 there was a serious drought that ravaged the country and because maize was not drought resistant as the African grains were, wide-spread famine caused pillaging of neighbouring clans and possibly even cannibalism in rare cases.

This was the time of Difaqane, which after several years of turmoil, virtually destroyed the Sotho-Tswana culture in the Magaliesberg and Dwarsberg areas. The Kwena settlement near Olifantsnek and the Hurutshe town of Kaditshwene in the Marico River Valley lay in ruins. The name Marico comes from the Tswana word ‘malicoe’ which means ‘drenched with blood’, referring to the battle that destroyed Kaditshwene in 1823.

Remnants of the stone-walled settlements built on the hilltops can still be found on and around the inselbergs in the northwest corner of Madikwe Game Reserve. These defensive sites date back to between 1800 and 1840.

The Boers

Andries Pretorius

Boers settled and farmed in the Marico River Valley, which they had wrought from Mzilikazi’s (a Zulu chief who resettled in the area) rule and consequently the Sotho-Tswana people, who had been enslaved by Mzililkazi, resettled in the area. Some Boers took to hunting for meat, skins and ivory, and when the elephants were shot out of the Marico area, moved north to Botswana and Matabeleland. A hunter’s road was established through the Madikwe Game Reserve to Derdepoort, and two wells at the top of the pass through the Tweedepoort Ridge were probably part of a resting spot for the hunters’ wagon trains. The infamous hunter, Frederick Courteney Selous, passed through Madikwe several times between 1875 and 1884 en route to Matabeleland.

In 1854 Andries Pretorius, after negotiations with the British, finally gained independence for the Zuid-Afrikaanse Republiek, comprising the area north of the Vaal River including the Madikwe/Dwarsberg area. Civil war between the Boer clans flared up during 1856 to 1864. In 1877 the British annexed the area, which was called the Transvaal. The annexation was rejected by the Boers and resulted in the Transvaal War (or First Anglo-Boer War) from 1880 to 1881. The Boers hung on to the Transvaal but in 1899 the South Africa War began, ending in 1902 after many battles, with the British taking control of the entire country.

In the northeast corner of Madikwe, fortifications date back to this period where the battle took place between the Boers and the combined forces of the British and BaKgatla. The Boers were caught unawares but when they returned fire, the British retreated and the BaKgatla were left to fight the battle on their own.

The Missionaries

During these years of turmoil, the Catholic Church in Rome established a Zambesi Mission in Matabeleland to cater for the Matabele descendants of Mzilikazi, now led by King Lobengula. Belgian priests of the Society of Jesus, Father Henri Depelchin (the leader), Fr Charles Croonenberghs and others set out on the long journey from Cape Town on the 16th April 1879. On 23 June they passed through the fertile Zeerust valley following the Mafekeng Road, which traverses the Dwarsberg and the main route northwards to Bulawayo in Zimbabwe. Five days later, they arrived at the Kalkfontein farm, where Fr Law nursed back to health a wounded farmer and explorer named Thomas Cocklin, who professed to have been the first white man to see the Victoria Falls.

With provisions replenished, the party set out over the Dwarsberg, the future site of the Madikwe Game Reserve, where they encountered – according to Depelchin’s letters home – flocks of ducks, herons, bustards, blue storks and ibis. They also saw kudu and other antelope, and heard cheetah, hyena, leopard and jackal. There were no signs of lion that, in 1836, English military engineer William Cornwallis Harris had encountered.

After crossing the Dwarsberg they came across a farm which looked like an ideal site for a mission. The priests continued past Derdepoort, along the Marico and Limpopo Rivers and eventually reached Bulawayo on the 7th July 1879, where they established a mission station.

Four years later, after several of the original party had died of fever, Depelchin decided that a mission station was needed in a healthier area, free from malaria, where the priests serving in Bulawayo could rest and recover from fever. The farm Vleischfontein, which had previously been ear-marked as a likely spot, situated on the Tweedepoort plateau on the Mafeking Road and measuring 4 000 morgen (about 8 000 acres), was purchased for 800 pounds, an exorbitant price at the time. Croonenberghs finalised the legalities of the transaction in Zeerust in October 1884 and building of the priest’s house began on the chosen site on the 8th December 1885, with the school being built in 1886, followed by the chapel.

The missionaries soon dammed up springs in which barbel were raised for Friday meals. A garden was also established comprising orchards and croplands. The Vleischfontein mission became a well-known landmark for those travelling on the Mafeking Road, many stopping to savour its hospitality, in effect making it the area’s first inn.

Remnants of a large Tswana community, mentioned in the mission’s correspondence, can still be found at the base of Tshwene Tshwene, the highest peak in Madikwe.

It was reportedly the 19th century capital of the BaTtlokwa under Chief Gaberone. Upright stones marked the residential zone, and a wide lane led from the grey cattle byres up to the chief’s residence. The chief’s area, or kgosing, was the only residential section that incorporated stone walling.

In June 1894, the mission was handed over to the Order of the Oblates of Mary Immaculate (OMI or Marists) as the Jesuits no longer needed a halfway house due to the building of the Botswana railroad. The Marists, together with the Holy Family Sisters (1914 to 1928) and Dominican Sisters (1928 to 1948) developed the school and built a church, a convent, a grotto and another priest’s house.

The original missionary priest’s house, a chapel, the grotto, a cemetery and some garden walls remain standing. Northwest Parks and Tourism Board are using the site for staff accommodation and the restored convent as their head office.

So after many years of turmoil and unrest the Madikwe area finally found peace and thereafter, followed years of economic growth in the area.